Now Moment: Selected Works by Sylvia Wald

A Centennial Celebration of the Artist’s Birth

Sylvia Wald (1915–2011) was a pioneer of the thrilling new landscape that was American modern art during and after World War II. Like many artists who came of age during the Depression, Wald’s early output was socially-engaged: she contributed illustrations to left-leaning journals and created drawings, prints and paintings that explored the plight of the working class, particularly disadvantaged African-Americans and those destabilized by the war.

But in the early 1940s, Wald met an exiled German-Jewish art historian named Justus Bier, who introduced her to Surrealism and other philosophical trends that had swept Europe before the war. Their intellectual exchange had a profound impact on Wald’s art, leading her away from social realism and into the realm of abstraction.

Wald’s earliest forays into abstraction found articulation in her prints. Wald had learned the technique of screen-printing following her debut 1939 exhibition at the venerable ACA gallery in New York, when a gallery staff member encouraged her to explore the medium. Screen-printing, which had historically been employed exclusively for commercial use, was just now becoming a vehicle of creative expression. Wald boldly experimented with her technique, pushing opaque and transparent paints, rather than ink, through her screens. She often would not make any preparatory studies for the prints, creating the composition straight onto her silkscreens.

The results of her technical experiments in the 1950s were astonishing: beautiful dendritic textures, arranged in harmonious compositions that possess the vitality of animate organisms or the psychic presence of a sentient being. Wald’s intuitive and bon chance process also ensured that each impression contained some variation, so even within a numbered edition each print is unique. Notable institutions such as the Museum of Modern Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art, began acquiring these masterpieces as early as 1951.

Between 1958 and 1961, Wald went through a brief period of gestural abstraction, creating frenzied scribbles in print and on canvas. Although there are a few extant paintings from her social realist period, Wald’s abstract oils on canvas comprise just this brief period of her mature oeuvre. The agitated feel of these canvases are altogether rather different from her other work—apparently an aberrant excursion for the easy-natured artist. The medium of painting, it would seem, did not satisfy Wald’s goals, for in the 1960s she put down the paintbrush and began almost exclusively working in three dimensions.

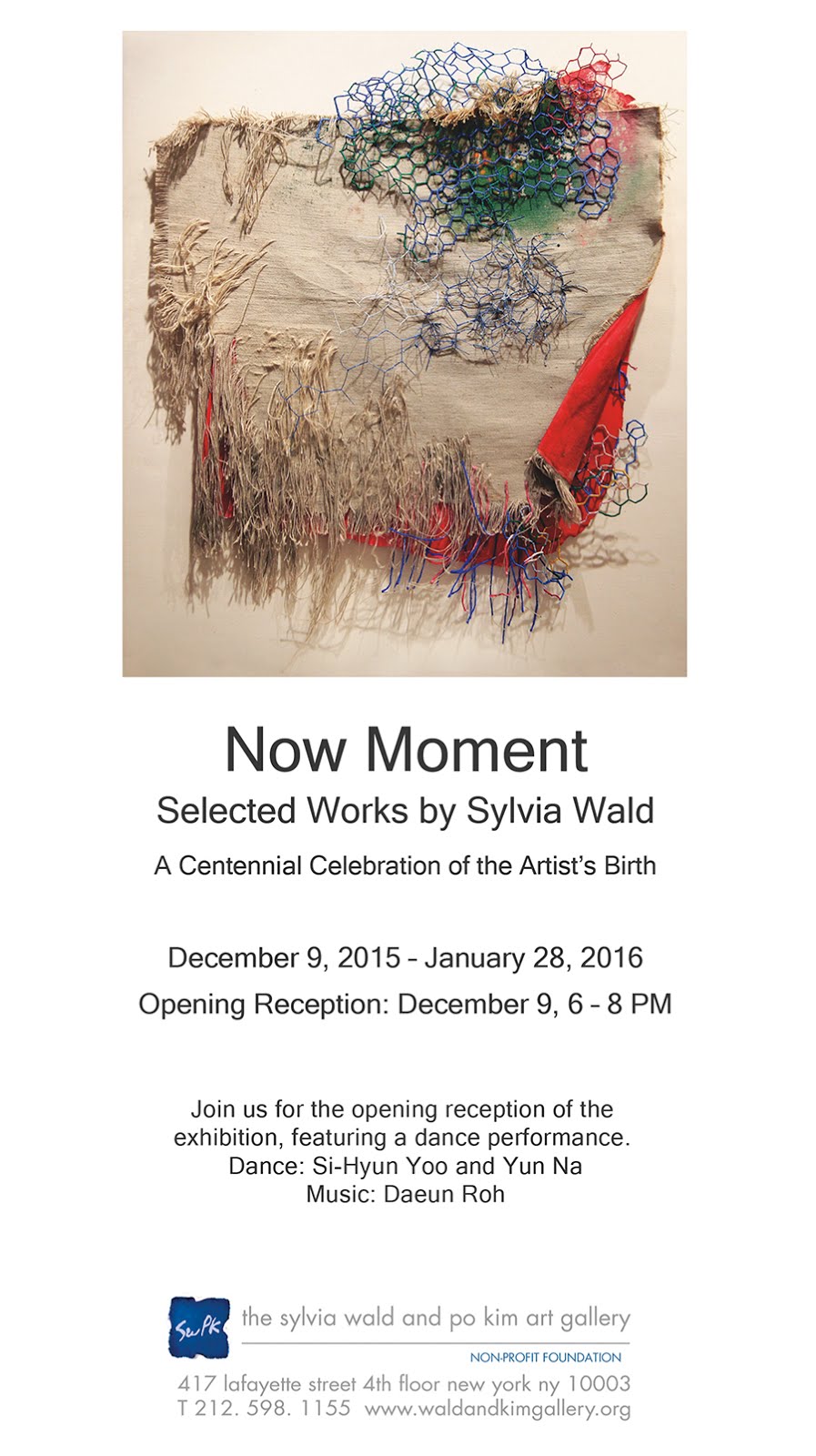

Wald’s new materials were wire, plaster, shredded canvas and paper, and found objects. The detritus of a New York City curb as well as that of the forested backyard of Wald’s country home all took on a second life in her artwork. In her mixed media sculptures and assemblages, Wald displays the same perceptive sensitivity to her chosen media that she did with her prints: a master’s facility with maneuvering the material to her needs, whilst maintaining a complete reverence for the natural tendencies of the medium. The artworks feel like present, living beings: the bright and coarse plaster is demanding in its immediacy; the wire and twine furiously map the synaptic connections of a poignant thought. The stubbornly insistent materiality of the sculptures only reifies their “being-ness.”

The metaphysical exchange between object and viewer can be likened to Eastern traditions of meditation and presence. Wald would undergo her own meditative contemplation of the essence of being, as evidenced by her studies and prints of simple objects. The Sleeping Dog and Pomegranate series, for instance, are powerful yet simple expressions on the being-ness of a dog or a fruit. Wald would more explicitly align herself with this Eastern philosophy in a work called Now Moment, which refers to the Buddhist core concept of presence: inner peace is achieved by being as present as possible in this very moment. The print has an embossed dimple the size of a dime, marked with a black dot no bigger than the head of a nail. The art can ask nothing else of us except our undivided attention to its simple composition: to be present with the dot, in this moment.

Whether Surrealistic abstractions or meditative studies of an object or figure, Wald’s art exerts its presence, and in our quiet exchange with it, we become increasingly aware of our own. Both beholder and artwork live in the now moment. On this occasion of the artist’s 100th birthday, perhaps she too is present with us now, as she once noted: “When you are this absorbed with it, it just all becomes part of you. So a lot of this is not conscious, it’s just there. It’s part of your being.”